Ant-fascist counter-protest in Sacramento last week

When is it OK to attack a Nazi? This should be a dumb question, but the Trump campaign has awkwardly placed this moral conundrum at the center of our political system. After months spent encouraging his supporters (including many Neo-Nazis) to assault protesters at campaign events, the inevitable has happened. Opposition is becoming organized and violent. People are showing up to stab the Nazis.

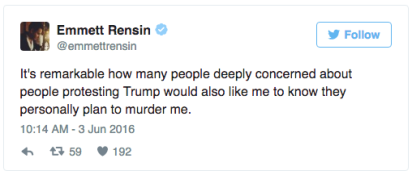

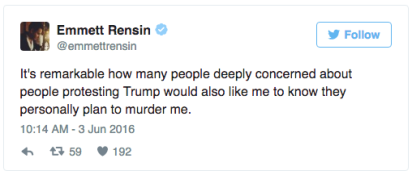

Rioting in Chicago in March was our first warning. At the end of April, Vox suspended its online editor, Emmett Rensin for encouraging protestors to riot at Trump rallies. Last week a group of Neo-Nazis in Sacramento staged a protest complaining of their treatment at Trump rallies. They were met by organized counter-protestors, resulting in a small riot and several stabbings. The genie is out of the bottle.

Until recently, the “is it okay to kill a Nazi” question would have been little more than an intellectual parlor game, a moral puzzle with only distant real world relevance. Ironically, the question “Would you kill baby Hitler” briefly became a campaign issue in our gonzo Republican primaries. It sounds dumb, but sitting beneath this goofy hypothetical is a revealing, and surprisingly complex ethical question. By what standard should we judge the morality of an act of violence?

Former Vox editor Rensin was fired for advocating riots at Trump rallies.

In other words, should I stab a Nazi?

Donald Trump is challenging our simplistic public narrative on political violence, building an entire campaign inside its contradictions. Forces he has unleashed now require us to develop a more sophisticated understanding of the meaning and morality of political violence – quickly.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. became an American civic saint for his categorical rejection of violence. Every year on his birthday we honor him by teaching schoolchildren that violence is morally wrong. He was, of course, murdered.

A few months later in June, we commemorate the D-Day landings. The carnage we unleashed in France was one of our finest moments as a civilization, an epic demonstration of courage, perseverance, and sacrifice for which we remain grateful and justifiably proud.

Violence is a moral outrage. Violence is the signal expression of our highest cultural values. Both statements are true, but neither is complete. They leave us with this conundrum: If it is OK for the US military to incinerate Hiroshima or Hamburg, then why isn’t it OK to stab a Nazi?

Civilization, one of our most vital evolutionary adaptations, is built on a logical fault line. At its simplest level, civilization is a social structure by which human beings harness formal, accountable, public violence toward the elimination of private violence. Civilization is designed to solve a human social problem – how do we live together in large groups without slaughtering each other? Adapting around that challenge in our social evolution creates an opportunity to more rapidly evolve technologically toward massive common benefit.

How do we leverage the enormous creative capabilities of a large community without allowing one or two people to simply steal it all or destroy our work? How do we capitalize on the power of a farm and an irrigation system without that work being ruined by marauders? How do we board a plane without yielding to our primal urge to club our way into first class?

The answer, paradoxically, is a combination of violence and non-violence. We use the powerful concept of legitimacy to create authority. We invest that authority with our collective powers of violence. Through those engines of legitimacy, whether based on heredity, ideology, religion, or a simple vote, we sacrifice a large portion of our agency.

In return for that theoretical transaction, we get to build a civilization. Instead of roaming the countryside eighteen hours a day searching for sustenance (and violently stealing it where we can), we get to live in permanent dwellings. We get to use technology to have better lives.

Boarding a plane looks like a triumph of non-violent human collaboration. It isn’t. Test the matter by violating one of the social norms governing that process. Take a place at the front of the 1st class line with your boarding pass marked “Boarding Group 4.” Set your watch. See how long it takes to experience legitimate violence meted out by the friendly security professionals who patrol the airport.

Everything we achieve through peaceful cooperation depends on our collective confidence that organized, legitimate violence will be available when we need it to enforce social and moral norms. Elevated by that understanding, we have developed cultural habits that make violence unnecessary in as many cases as possible. You can judge the sophistication and success of a civilization by how much public resource it takes to suppress private violence.

There was a genius to Dr. King’s campaign of non-violence which is seldom if ever noted. Without access to violence, King would have been killed far earlier, before his work had achieved any progress. By carefully restraining their resort to private violence, King’s movement created enormous pressure on our civilization to use public violence in defense of basic public norms and established laws. A disciplined restraint from unaccountable violence formed a successful moral appeal for intervention from disciplined, accountable forces.

King didn’t defeat segregation with non-violence. Jim Crow died at the sharp end of a bayonet. King’s genius was that he, and his followers, had the discipline, determination, and intelligence to refrain from wielding those bayonets themselves. That’s how he took his place as a latter-day Founding Father.

A victory for non-violence in Mississippi

Non-violence did not place James Meredith in a classroom at Ole Miss. Truckloads of US soldiers did that, deploying in overwhelming force to defeat resistance. Losing track of the violence that propelled the Civil Rights Movement to victory obscures its lessons.

As in King’s time, there is an accountable political structure currently in place charged with protecting us all from violence by Trump supporters, Trump opponents, or anyone else. Like in King’s time, that structure is struggling to adapt to the challenge posed by Trump’s unprecedented appeal to private violence. Just like the scenario King faced, a resort to private counter-violence will degrade the capacity of that central authority to do its job. Restraint will make the lines of demarcation clearer, allowing that central authority over time, to leverage violence as needed, if needed, to bring a just outcome.

Above the fray, the political process is slowly working to strangle the Trump phenomenon, pressing it to the margins toward political defeat. In short, the system is working. So-called “protestors” stabbing Nazis at rallies are not doing us any favors. They are just one more problem to be ultimately solved by law enforcement. Private violence will eventually yield to public violence if necessary in defense of order.

We hanged John Brown. Jefferson Davis was allowed to live. The reason is simple. Brown was leveraging violence outside of any negotiable structure. Brown was the rough modern equivalent of a terrorist. Think what you will about his purported cause, Brown was first and foremost a killer convinced he was taking orders from God. Like modern terrorists, John Brown’s politics were incidental to his violence. He could not inhabit a civilization.

Like the rebels who founded our democracy, Davis was operating inside of a reasonably accountable authority structure. His cause was abhorrent, but he and his compatriots pursued that cause through a channel that civilization could ultimately cope with, defeat, and tolerate. That structure granted one critical benefit to his enemies that Brown did not offer – negotiability.

Davis could be (and was) persuaded to terminate his violence through a combination of counter-violence and politics. His cause notwithstanding, Davis’ resort to political violence was less of a fundamental threat to civilization than John Brown’s. That accountability to a defined political structure meant that Davis’ violence could be contained and ended without necessarily killing him.

Davis didn’t commit any acts of violence after the war. No one was ever going to stop John Brown from killing, no matter what happened in the political realm.

Violence unleashed by amateurs in the streets, accountable to no one, cannot be contained through politics. The kind of people who will be rioting at Trump rallies over the next few months are not working toward a political goal. They are doing what they like to do. People who leverage this kind of violence, like Trump or Rensin, are a cancer on civilization.

Someday, under some circumstances, perhaps it might be necessary to kill a Nazi. If it is ever again done legitimately, that violence will be constrained by defined goals and a negotiable authority structure.

What happened in Sacramento is not politics, it’s just violence. That kind of violence always looms at the margins of civilization. Releasing it into our political bloodstream takes us in unpredictable, unwelcome directions.

Please refrain from stabbing the Nazis. Other people will do it better and more thoroughly than you should the need arise.

“In individuals, insanity is rare; but in groups, parties, nations and epochs, it is the rule.”

“In individuals, insanity is rare; but in groups, parties, nations and epochs, it is the rule.”

“Although I’m certain that no politician or terror expert would agree, I suspect that this kind of chronic low-level terrorism may be a permanent feature of metropolitan life.”

“Although I’m certain that no politician or terror expert would agree, I suspect that this kind of chronic low-level terrorism may be a permanent feature of metropolitan life.”