Wise people avoid expounding on issues they do not grasp. In that spirit, you’ll find very little content here on foreign policy, military life, Canadian politics, bow hunting or hockey, as a small sample. Occasionally though, an issue is so important that it can’t be ignored merely due to ignorance. Sometimes it’s helpful just to describe the outline of a baffling problem in the interest of generating conversation that might lead to clarity.

Privacy issues emerging from our ever expanding digital lives are so complex and unprecedented that it’s difficult to establish any useful reference points. Clearly we are making policy decisions in our time, mostly by default or inaction, which will determine the shape of our personal and property rights in the digital realm for generations to come. We are making these decisions (and in-decisions) while largely blind to the outcomes and implications. That’s not just frightening, it’s maddening, and there doesn’t seem to be much that we can do about it.

Part of the problem is that privacy as a legally protected “right” is rather new. The Bill of Rights mentions some of the building blocks of privacy, including the obscure 3rd Amendment, but there is no expressed privacy right in our Constitutional law. The first time the Supreme Court struck down a law for interfering with privacy was in 1923.

In Meyer v. Nebraska the Court invalidated a state law criminalizing foreign language instruction in primary schools. This reading of the liberty clause in the 14th Amendment was novel. The decision did not use the word “privacy” but described the concept at some length. By interpreting 14th Amendment protections to extend beyond mere physical constraints, the Court was beginning to stake out a realm of personal space protected from public interference.

It was a reasonable response to the nation’s transition from an agrarian to an industrial culture. The concept of privacy is fairly esoteric when your nearest neighbor lives too far away to see. Liberty has different demands in a city.

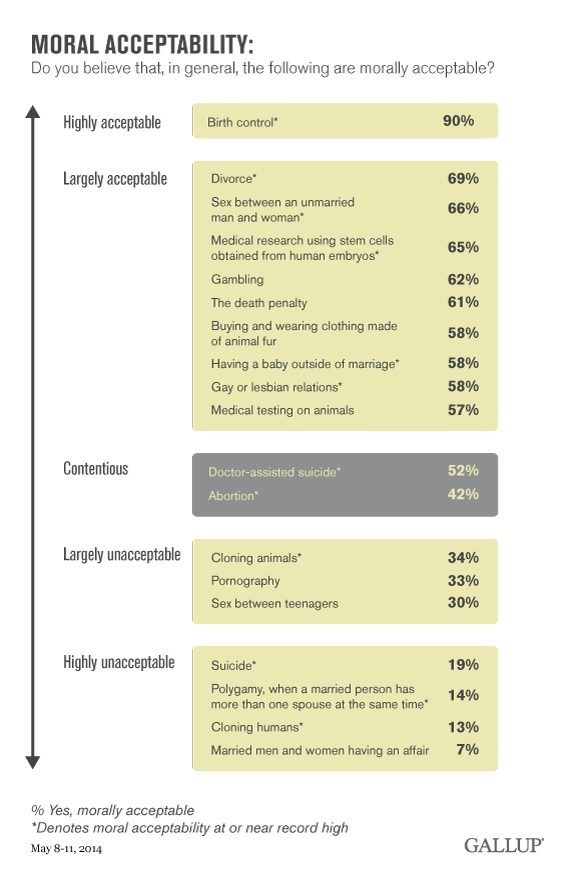

Even then, another four decades would pass before the term “privacy” would take on much meaning in legal terms. Griswold in 1965 and Roe in 1973 established privacy as a personal, Constitutional right in rulings dealing with contraception and abortion. Even then those decisions were controversial and privacy rights are still contentious. As late as 1989 the Bush Administration nominated a Supreme Court justice who denied a Constitutional privacy right. The matter was not generally settled until the Lawrence decision in 2003. You can still find prominent Republicans who insist that the Constitution does not protect personal privacy.

Privacy as we generally understand has come more from legislation and culture than from Constitutional law, reflecting the fact that commerce, not politics, is where our privacy is mostly in play. The Fair Credit Reporting Act was passed in 1970, representing probably the most powerful protection of personal financial information. Your rights to your health data were not uniformly protected at the Federal level until 1996. Privacy legislation has been late in arriving and relatively thin compared to other western countries. New technological developments are already rendering our meagre protections useless.

A new generation of credit reporting companies is emerging to evaluate your value in the digital realm. Everything from your home equity to your social media influence is available for assessments that impact your ability to get a job, borrow money, or engage in other commerce. Refusing to participate in social media or other methods of surveillance does not prevent the creation of a profile, it merely influences your score (downward, generally).

Almost none of this category of surveillance is covered by existing consumer protections or credit regulations. The monitoring of your email and phone metadata by the NSA is positively trivial in size, sophistication, scope, and relevance compared to the dossiers being compiled on you by Internet service providers and other technology companies, free of almost any accountability or regulation.

Traditionally, transparency and consent have been treated as the antidote to privacy intrusion. Law assumes that the real tension in privacy disputes comes not from surveillance, but from clandestine surveillance. To the extent we are properly warned of what is being done, an activity is largely accepted. That understanding may not be enough as our technology becomes increasingly complex.

There are things you would say on a train that you would not say in an elevator. There are things you would say on a softball field that you would not say at school. There are things you would say in a break room that you would not say in a conference room. We expect to be able to judge fairly sophisticated grades of our setting in order to judge what levels of candor or expression will be not only appropriate, but properly understood by a potential hearer. That is one reason that so-called “hearsay,” an over-heard third-party report of a statement, is generally inadmissible as evidence in a legal proceeding. There is no similar protection from the impact of hearsay online.

At stake is not merely our control of our image, but our ability to communicate effectively. Use language or phrasing appropriate for the bleachers at Wrigley Field at a 3rd grade softball game and witness one of the challenges presented by the decline of privacy. The ability through omnipresent surveillance to transpose communications from one setting to another without context can have implications for one’s ability to hold a job, protect a credit rating, influence politics, or retain ownership of the Los Angeles Clippers. Watch how many phones are recording the speeches at the next political meeting you attend. Why is that happening?

We are less and less competent to judge the sensitivity of our communications as surveillance technology transforms the landscape. What makes this phenomenon so difficult to manage is the fact that its implications are entirely mixed. Yes, a central authority can now monitor your every move. However, you may also monitor theirs. The technology that lets the police identify a suspect on the street can (and occasionally is) also used to observe and punish police brutality. Technology that lets someone surreptitiously record your conversation also lets you photograph the person who stole your phone.

Adding to the complexity is the fact that surveillance is not merely, or even primarily, a matter of state power. Say what you will about the Snowden leaks, but perhaps the most startling revelation from the whole affair is the discovery of how far the Federal security infrastructure still lags behind the monitoring capabilities of private companies.

The potential for government to misuse personal information is a valid concern, but it is far from a pressing concern. What looms over us now is the digital land grab that is gobbling up property rights in information that could potentially belong to individuals. When those rights are gone they will never be restored.

Your digital profile is valuable property. Like a homestead on the prairie that you haven’t seen yet, it may belong to you, but it is very difficult to evaluate. Our current model allows individuals to sell away chunks of their privacy rights in exchange for free email, navigation services, games and hundreds or even thousands of other valuable services.

The freedom to transfer those rights is every bit as constitutionally valid as a right to privacy. The problem is that technology companies are operating at a significant information advantage as relates to individual consumers. Like oil companies at the turn of the 20th Century negotiating leases with farmers, both sides are engaged in an uncertain speculation. However, without any legal framework to set the balance the companies control the terms of the trade. Ask a landholder what it takes to recover their mineral rights and you’ll get a sense of what the next generation faces online.

So what can we do about this? In the digital realm, what is “privacy” and how valuable is it? How much of your data should be protected? On what terms should you be able to bargain it away? I don’t have answers and I’m not seeing a lot of other good ideas. There is no partisan divide on the issue of digital privacy as there aren’t really any coherent positions being taken by anyone on a broad scale. It might be the most important issue rights issue of our time and we have little or no idea what to do with it.

At the very minimum, it is probably necessary to remove the ability for children to sign away their digital rights while still a minor. A generation is emerging that values privacy in much the same way they regard virginity, as something to be shed definitively in the transition to adulthood. That is a completely unnecessary mistake and we owe it to our children to prevent it. Blocking the compromise of privacy individually is like trying to build seawall around your beach house. To be practical and effective, this will have to come from legislation.

The terms of the compromise struck at age 13 may look very different at 30, but perhaps not. Privacy, like mineral rights, may be meaningless if you never knew you had it in the first place. If all we do about the erosion of our ownership in our personal profile is to build a wall around an emerging digital generation that might be enough. Perhaps an emerging wave of digital natives with a keener understanding of technology might strike a different collective bargain for their digital rights.

For us, there seems to be very little we can do to establish any personal control of our online data. We’ve made our bargain for free real time maps and music. The value is not trivial, but it will likely prove to be a fraction of what those assets were worth. No matter, we will get where we are going on time and be entertained along the way even if the destination is unknown.